People say that perception is the new reality. In fact, perception guides our behaviour in the new norm. What’s interesting is that the strongest link between perception and behaviour is sentiment. That said, sentiment collectively influences our final behaviour.

What are the underlying reasons behind public sentiment during this global pandemic? Can social media sentiment provide further insights?

Before we share our findings, let’s take a brief moment to reflect the situation that we are in.

The world is more connected than ever before.

Social distancing and lockdowns around the world have led to a massive spike in online media consumption, which includes time spent on social media platforms. New research by the World Economic Forum showed between 80% and 90% of people consume news and entertainment for an average of almost 24 hours during the global pandemic.

96% of the global population reads, watches or listens to news and entertainment

World Economic Forum

As COVID-19 spreads globally, social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter, which barely existed during past major outbreaks, are enabling crucial conversations about the virus, and at the same time allowing sensationalism and misinformation to spread faster than the speed of light.

And lest we forget, almost all mainstream news are now on social media platforms too.

Trapped in a mass of self-communication within our social media bubbles, our perception changes rapidly depending on how much and what exactly we know. Our brains are programmed to process visual stimuli faster than sound – hence the flurry of images and attention-grabbing news headlines can easily shape how we feel about an event or issue.

Getting further away from reality

The danger of being overly connected on social media is the deterioration of our own ability to distinguish between reality and what was presented online.

We constantly share online content that fuel an irrational panic, feed our anger and other negative thoughts without understand the context, or worse, checking its authenticity – thus pushing us further from reality.

To put things in perspective, a recent experiment by two Danish photographers below illustrates the power of visual perception during COVID-19 and how this can have a profound impact to public sentiment.

Image credits: EPA / Philip Davali / Olafur Steinar RyE

Image credits: EPA / Philip Davali / Olafur Steinar RyE

Which of the pictures above generate the perceptions of fear and panic?

Taken from the same location on the same instant, this simple experiment showed how we are easily influenced by what we view.

With myriad of content being generated on social media every second, there is no way we are able to distinguish what is real and what is not. Regardless, the mass flow of information and misinformation are drawing large amounts of conversations and user engagements.

Thanks to data science, our analysts are able to visualise sentiment changes from social media users in Malaysia using millions of social data across 8 different online platforms in multiple languages.

Using advance social analytics and machine learning text algorithms, we are able to detect sentiment changes based on social media conversations and posts during the COVID-19 lockdown – also known as the Movement Control Order (MCO) period in Malaysia.

So here is a glimpse of public sentiment on COVID-19 based on social media data and posts captured over a period of 40 days.

Social sentiment is unusually erratic during a crisis

How we feel can be measured based on what we post, or what we wrote on social media platforms – and the bulk of our action is tightly connected to our brains.

Whether we use each or both sides of our brains to process information – it leads us to form an opinion, it reaffirms our judgement and thoughts, and it enables us to undertake a specific set of actions and responses.

Now, the interesting part is, because we are humans with inherent anxieties – how we feel changes all the time, even down to the seconds.

Information dissemination travels at a faster rate during a crisis – algorithms working overtime causing unusual spikes of sentiment polarities – resulting in a positive sentiment or negative sentiment depending on events of the day.

Our study found that the mainstream news had caused a healthy wave of conversations while at the same time widening the polarity of opinions between social media users – depending on the headline and imagery used.

At the same time, self-communication from self-generated content largely fuel a mix of laughter and joy during the MCO.

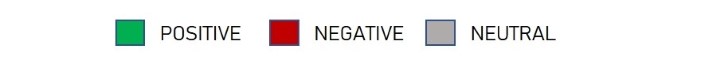

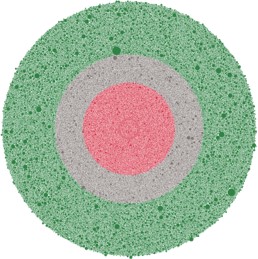

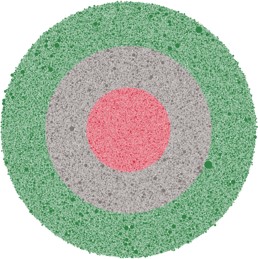

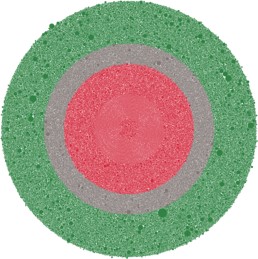

Weekly snapshots of sentiment by social media users during the COVID-19 lockdown, that is, the MCO period, showed better clarity of the sentiment changes.

Weekly Sentiment Analysis on COVID-19

Week 1: 16th – 20th March 2020

Total mentions (n=910,079)

Week 2: 20th – 27th March 2020

Total mentions (n=1,692,063)

Week 3: 27th – 3rd April 2020

Total mentions (n=940,483)

Week 4: 3rd – 10th April 2020

Total mentions (n=782,934)

Week 5: 10th -17th April 2020

Total mentions (n=800,973)

Week 6: 17th -24th April 2020

Total mentions (n=593,798)

Figure 1: Net Sentiment of social media users during COVID-19 lockdown period (N=5,720,330) based on weekly analysis. Source: Berkshire Media team analysis.

Key insights:

- Sentiment changes daily and is unusually erratic depending on the hour of the day. Steady state occurs at midnight when users are less active on social media platforms.

- Significant changes were due to polarity of opinions generated by social media users from various news, policy announcements and events that are largely politically-motivated.

- Fiscal policy announcements such as the economic stimulus-package and socio-economic stories created more conversations and widening polarities between the middle and middle upper income household users, and the low-income household users.

- Preventive health measures continue to attract a wide audience as empathy and positive well-being cuts through all level of income segments.

- Fear-induced news headlines draw more user engagement and user reaction compared to neutral or positive-toned headlines.

- Content related to entertainment, sports, religion and food generally bind people together amid adversity with a strong positive sentiment – driven by collective empathy and the camaraderie of communities.

The underlying psychology behind sentiment

Let’s dive deeper on the underlying psychology behind sentiment analysis from social media and here is a question:

What drives you to wake up every morning and rush to the office?

If your answer is centered on wants and needs such as “I need to put food on the table for my family”, or “I am out here to achieve something good”, then you miss the point.

At the heart of our activities today is our primal fear – one of six primary emotions, that is responsible to propel our existence today.

The underlying psychological behaviour of you waking up daily and rushing to the office may be due to any of the following fear-induced categories:

- fear of losing your job or getting fired

- fear of not completing your job on time

- fear of not being recognized by your peers as a team player

- fear of not being promoted by your boss

Now, here is a better illustration.

Fear of death shapes how we avoid danger while fear of losing motivates us to achieve the things we aspire (e.g.: having the latest iPhone, aiming for the next job promotion or bonus).

The resultant of fear of losing or fear of death elicits more automated responses based on what is processed in our brains.

In fact, multiple studies have shown that fear can elicit more negative-skewed responses on social media. In the case of COVID-19, this can be seen in the form of criticism, expressions of hate, disbelief and others.

A social media sentiment study by the University of Duisburg-Essen in Germany showed that social media users respond to negative posts more than neutral or positive events in social media.

Much of this fear is equally influenced by our own self-interest, belief-system, community or political affiliation within the social media bubbles that we live in.

Our past experience in sentiment analytics and emotion analytics showed that headlines from the media play a significant role in shaping public sentiment and the overall perception.

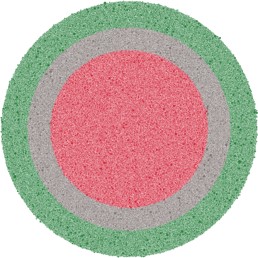

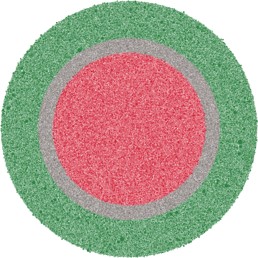

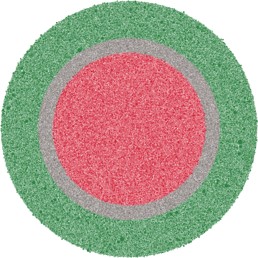

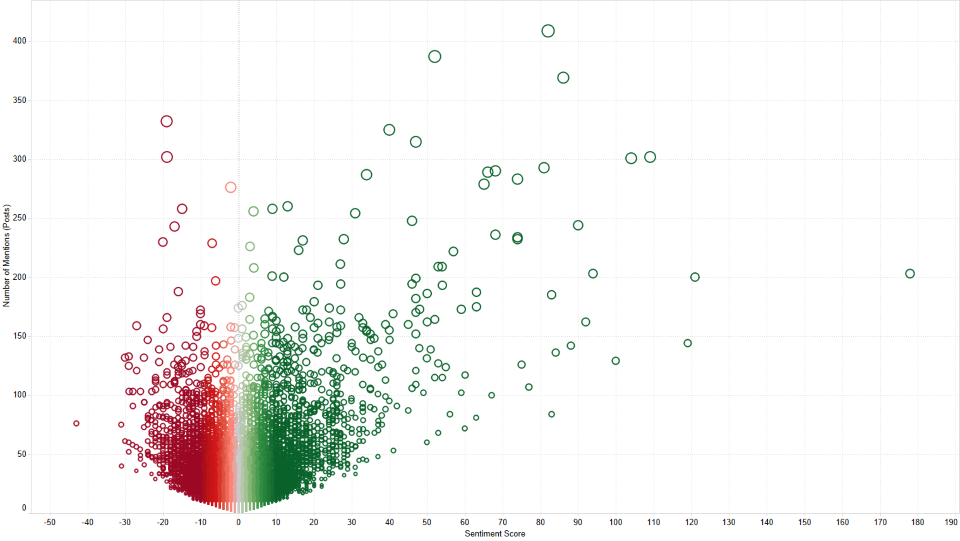

Figure 2: Net Sentiment Score for each social media account (i.e users and authors) on COVID-19 in Malaysia (n = 5,720,330). Each circle represents a unique social media user or account. Source: Berkshire Media team analysis from 16th March until 24th April 2020.

As fear of unemployment and concern over job security is on the rise during these challenging times, fear pushes the whole system into overdrive. As far as one’s fear is concerned, there are only two possible outcomes to COVID-19: either you get out of the crisis alive, or it won’t matter because you will be dead somehow.

However, the psychological chain reactions triggered by fear are often anything but simple. Our world today is full of complicated new problems or challenges that misperceive our reptilian fear response.

As fear is one six primary emotions, measuring emotions from social media becomes an increasingly important tool that allows decision-makers to understand the underlying psychological drivers besides anticipating the right policies or narratives to manage reputation risks during a crisis.

Misinformation Fueling Sentiment

An important takeaway from measuring public sentiment on social media is how misinformation can easily spread like a bushfire – more so with politically-motivated intent to widen the polarity of opinion by fueling sentiment either way (i.e. highly positive or highly negative).

The article from the TIME rather aptly describes the situation of misinformation in the world of social media that we live in.

“With contradictory information about COVID-19 emerging from the highest levels of government, disinformation experts say it’s more important than ever for those with accurate information to be sure they’re being heard. That’s easier said than done.

The algorithms that shape what we see on social media typically promote content that garners the most engagement; posts that draw the most eyeballs get spread farthest.

Researchers say that model is partially responsible for the spread of misinformation and sensationalism online, since shocking or emotionally-charged content is especially good at getting people’s attention.”

Closing Thoughts

The social media world has evolved into complex behavioural nodes that are interconnected with our psychological drivers and largely influence how we feel about the current situation.

While access to information is no longer a challenge, subscribing to trusted content in an array of misinformation requires continuous education from policymakers and self-realisation from netizens.

The global pandemic and self-isolation have taught companies and policy makers an important a lesson in managing crisis – ensuring fact-based communication reaches out to the social media users in order to manage public sentiment.

In reality, this will continue to be a challenge in a user-generated content environment; a social media world that is self-governed by automated algorithms that few of us has access to.The poet and novelist, Ben Okri, writes

“It may well be that it is not only self-isolation and science that saves us. We may also be saved by laughter, by catharsis, by the optimism of being able to see beyond these times, with stories, with community, with songs.”

As sentiment irregularity from a crisis presents new opportunities to manage reputation risks for brands and companies, regular sentiment analysis from social media monitoring becomes a handy data-driven tool to ensure brand loyalty is retained once the crisis is over.

In the absence of real contact and interaction, the integrity of media and data-driven insights from social media has never been more relevant.

About the Author

Shahid Shayaa is the founder and managing director of Berkshire Media. He specializes in data-driven communication strategies and insights using social data analytics, social media monitoring tools and machine learning text algorithms for more than 13 years. As an expert in the field of media monitoring, issue management and reputation risks for companies, his deep involvement in various research studies in this field and published various scientific papers on social data analytics, sentiment analysis and back-end algorithms on consumer sentiment, emotions and behaviour for marketers and campaign managers.